Sparking Interest for the Arts of East Asia

On the History of the East Asian Art Society in Berlin

(1926–1955, re-established in 1990)

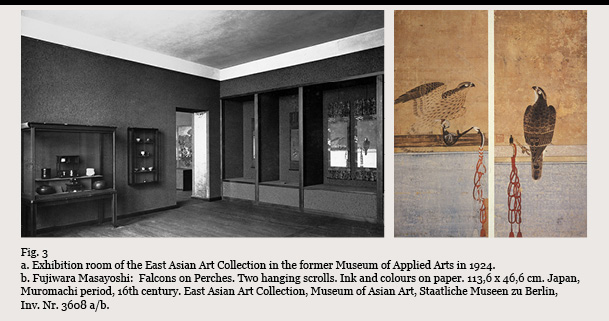

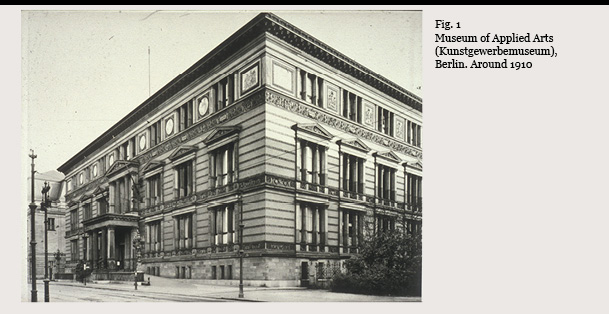

In 1926, two years after the opening of the first permanent galleries of the East Asian Art Collection in Berlin, the East Asian Art Society (Gesellschaft für Ostasiatische Kunst) was founded. The foundational meeting with 61 members took place on January 23, 1926, in the Berlin Art Library (Kunstbibliothek), adjacent to the building where the East Asian Art Collection was housed, the “Museum in der Prinz-Albrecht-Straße”, the former Museum for Applied Arts (Kunstgewerbemuseum), today’s Martin-Gropius Building (Fig. 1).

The East Asian Art Collection was founded in 1906 already as an independent department of the Royal Prussian Museums in Berlin and began from scratch. It took almost two decades until a permanent exhibition of the collection could be established in the Martin-Gropius Building. Wilhelm von Bode (1845–1929, fig. 2), Director General of the Royal Prussian Museums was the founding father, Otto Kümmel (1874–1952) its first director.

The East Asian Art Collection was founded in 1906 already as an independent department of the Royal Prussian Museums in Berlin and began from scratch. It took almost two decades until a permanent exhibition of the collection could be established in the Martin-Gropius Building. Wilhelm von Bode (1845–1929, fig. 2), Director General of the Royal Prussian Museums was the founding father, Otto Kümmel (1874–1952) its first director.

Also illustrated is the art dealer Hayashi Tadamasa (1853–1906, Fig. 2 ), active in Paris and Tokyo. Parts of his collection formed the basis of the Berlin museum. The innovative layout and the interiors of the new museum (Fig. 3) were immediately noted for their “East Asian” proportions and design. The number of objects on display at a time was reduced to an agreeable measure and the works of art were exchanged from time to time. Exquisite paintings were displayed in niches with wooden framework. Features of the Japanese house were thus put to use in a museum context. The presentation – acclaimed for its nobleness and serenity – was a new approach to familiar visual habits (“Sehgewohnheiten”) in the German museum world and met instantly with enthusiasm by the critics.

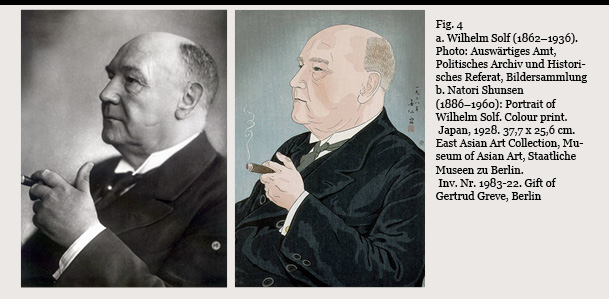

Thus the setting for founding the Society in 1926 was perfect. At the foundational meeting Wilhelm Solf (1862–1936, Fig.4), the German ambassador in Tokyo, who was also a dedicated collector of Japanese prints was elected as president, an office which he held for ten years. The Japanese print with his portrait was executed by Natori Shunsen (1886–1960), famous for his Kabuki actor portraits.

The Society aimed to foster a deeper understanding of the arts of East Asia und to support the East Asian Art Collection. Within the next decade the Society flourished, and membership numbers rose around 1930 to more than 1000. Pioneering exhibitions organised by the Society in collaboration with the Prussian Academy of Art enormously fostered the appreciation for the Arts of East Asia in Central Europe and contributed to the stunning success story of the East Asian Art Collection. Already in 1912 Otto Kümmel had also founded together with William Cohn (1880–1961, Fig. 5) the East Asian Journal (Ostasiatische Zeitschrift) which was to become the leading journal for East Asian Art in the West and which continued to be published until 1943 (re-launched in 2001). Kümmel was particularly successful at attracting private collectors as donors and benefactors to the Museum. The Meyer-Grosse collection comprising more than 500 objects was finally bequeathed to the Museum in 1915. In 1919 the large collection of Gustav Jacoby with some 1500 objects including excellent pieces of Japanese lacquerware and sword fittings was given to the museum.

Berlin Emerging as a Centre for Collecting East Asian art before World War II

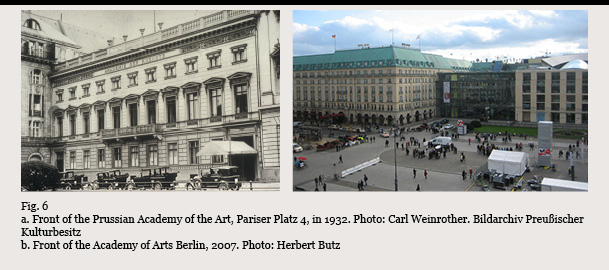

Three years after its foundation, the Society launched the landmark exhibition of Chinese art under the auspices of the Prussian Academy of Art on the premises of the Academy on Pariser Platz next to the Brandenburg Gate (Fig. 6).

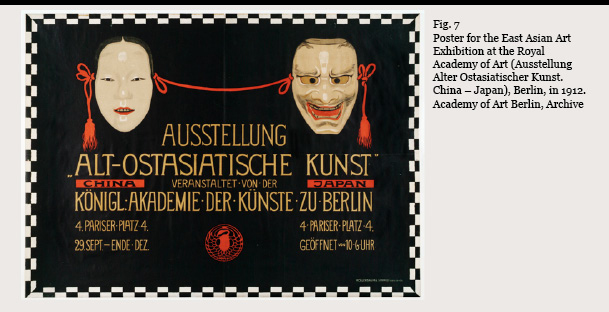

The cooperation with the Academy and the perfect location of the exhibition halls on Pariser Platz was an excellent strategy of Otto Kümmel and the Society. Already in 1912 Kümmel had successfully organised an exhibition in cooperation with the Academy. It was the first major show of East Asian Art with 1,122 exhibits among them 417 Japanese sword fittings and 209 woodblock prints (Exhibition of old East Asian Art. China – Japan/Ausstellung alter ostasiatischer Kunst. China – Japan) (Fig. 7).

Not only did the young East Asian Art Collection use this exhibition as a platform to highlight its treasures but private collectors were also encouraged to take part. Thus the major collectors of East Asian Art in Germany at this time already mentioned as later donors to the museum, the Japanese consul in Berlin, Gustav Jacoby (1857–1921) and the Freiburg collectors Ernst Grosse (1862–1927) and Marie Meyer (1834–1915) also contributed to the show. It was well received internationally and prompted further cooperation with the Academy of Arts in later years.

Most successful was the cooperation with the Academy in organising the landmark exhibition of Chinese Art in 1929. The exhibition was a huge effort for the collection and the Society and Otto Kümmel was strongly supported in this event by his staff member Leopold Reidemeister (1900–1987, Fig. 8) and others.

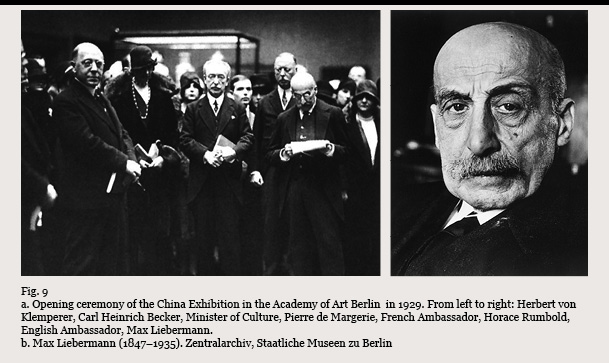

The celebrated painter Max Liebermann (1847–1935), president of the Academy, opened the exhibition (Fig. 9), which he regarded as the single most important event of the year, on January 12, 1929. For the first time in Europe, the attempt was made to present Chinese art in its full range with the exception of Architecture and to give as complete a view as possible with the art works available.

The celebrated painter Max Liebermann (1847–1935), president of the Academy, opened the exhibition (Fig. 9), which he regarded as the single most important event of the year, on January 12, 1929. For the first time in Europe, the attempt was made to present Chinese art in its full range with the exception of Architecture and to give as complete a view as possible with the art works available.

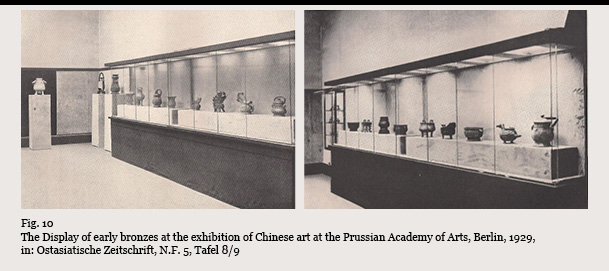

The exhibition attracted almost 60,000 visitors and included about two hundred early Chinese bronzes and jades among the total number of 1,250 exhibits which were regarded as the “inner sanctum” of the show (Fig. 10).

Collectors of high renown came from near and far: R.H. Hobson from the British Museum with the collectors Sir Percival David, George Eumorfopoulos and Oscar Raphael and the Swedish Crown Prince, the later H.M. Gustav VI Adolf, King of Sweden (1882–1973). He examined and handled exhibits at the Academy each day for one week before the opening hours.

The English scholar and merchant Francis Ayscough (1859–1933), husband of the American poet and translator of Chinese literature, Florence Ayscough (d. 1942), visited the exhibition and wrote an imaginative short prose piece based on selected objects in the exhibition with the title “Phantasmagoria”. It was published in English in the journal for Far Eastern Art, the Ostasiatische Zeitschrift (N.F., 5. Jg., Heft 2 (1929), pp. 46–48) and is a fine testimony to the strong appeal of the exhibition and in particular its excellent array of early Chinese bronzes. Ayscough chose 12 objects from the exhibition which he imbued with life in a poetical way. I would like to illustrate this by introducing three of the objects from his very special poetical past midnight guided tour of the exhibition. He begins by leading the reader to the site of the exhibition and focuses mainly on the galleries where the early Chinese bronzes were displayed:

Florence Ayscough: “Bare black branches are outlined against a waning moon; midnight has passed, and the hour of icy dawn is not yet here; the Platz is silent. Behind the shining doors of the Akademie, beyond the marble stairs, is solitude, and yet there is the flutter of movement, the breath of voices – voices issuing from strange and varied shapes, voices which speak of happenings long past, of centuries long dead.

In chorus the wine vessels, the incense burners, the cooking pots and the bells describe great sacrifice held in the feudal days of Chou; then speak of their present habitat far from the Central Flowery State.”

Ayscough (Fig. 11): “The rams spoke first, those grave beasts who, standing back to back, support on their pearly haunches the vessel which once held sacred spirit made from grain: ‘We, the trustworthy, who stored the sacred wine, now look out through mists which rise from the river Thames. Our wine vessel is empty, but we will bear unflinching through ages to come the grave responsibility laid upon us by those who cast our forms three thousand years ago.’”

Ayscough is referring to the fine Bronze ritual wine vessel in the shape of a pair of rams supporting a jar, dating to the Shang period (13th to 12th century BCE) which was on loan to the exhibition from George Aristides Eumorfopoulos (1864–1939), the Greek merchant and art collector, today in the British Museum. Ayscough continues by highlighting the famous wine vessel, Guang type, from the collection of the American journalist and art patron Agnes E. Meyer (1887–1970) and her husband, the banker Eugene Meyer (1875–1959), today in the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.

Ayscough (Fig. 12): “The horned bronze beast gnashed his teeth and rattled the shining spines with which his maker had adorned him so lavishly, yet with so sure a hand; he spoke saying: ‘I who poured the wine you stored, now rest in a new land, one where the people, young and strong in their enthusiasm for the future, yet love to stare into the past; for them I speak of rites long dead, of reverence, of an indissoluble link with men who have passed to the Nine Springs in the World of Shade – and they, these young people, respond.’”

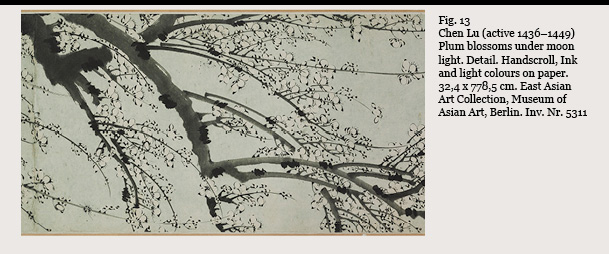

Ayscough concludes his prose piece by illuminating a very fine Chinese painting in the exhibition from the Berlin East Asian Art Collection, which Otto Kümmel had acquired in Beijing only two years before in 1927 (Fig. 13). It is a magnificent handscroll by Chen Lu (active 1436–1449): Plum blossoms under moon light, ink and light colous on paper, 32,4 x 778,5 cm, of which a detail is illustrated

Ayscough: “Suddenly, the acrid fragrance of plum-blossoms filled the room; a great tree with gnarled, wide-spread branches filled the space which had been the wall.”

And then the tree begins to speak:

Ayscough: “Ch’ên Hsien-chang [i.e. Chen Lu] loved me; he sat by moon-light in the fragrance of my white cascade, by sunlight watching the blue sky through the Spring cloud of my petals; and then one day, illuminated by wine, he was able to write my beauty on this scroll. Now, what was my body, has vanished, but this, my portrait, remains for ever: a testimony to the vital spirit of man and to him who recognized it as he passed.”

And finally Ayscough ends his prose piece: “The pale light of icy dawn touches the bare branches in the Platz; the city stirs: in the Akademie, silence.”

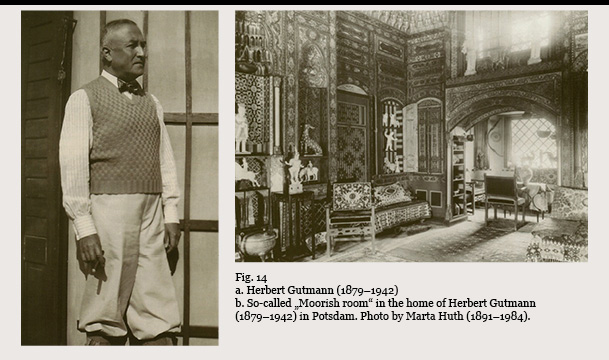

Collecting Chinese art was very much en vogue in Berlin in the Twenties. It is most instructive to have a closer look at the list of lenders to the great Chinese exhibition of 1929 which could also be interpreted as a kind of performance show of private and public collections. 165 public and private collections contributed loans to the exhibition. 75 among the private lenders were from Berlin. Chinese ceramics was still one of the most popular fields of collecting. The banker Herbert Gutmann (1879–1942), member of the board of the East Asian Art Society, contributed pottery and porcelain figures from his collection to the exhibition. Some of his pieces can be seen in a photo by Martha Huth who photographed Berlin Interiors of the late Twenties. One of the – still extant – rooms in the home of Herbert Gutmann in Potsdam with Islamic wall panelling was called “Moorish room” (Fig. 14) and its niches served for presenting his Chinese collection.

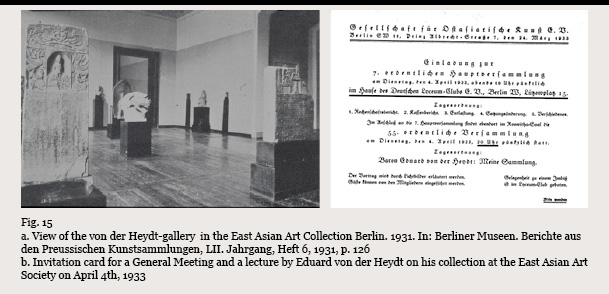

In the early 30s one of the patron members of the East Asian Art Society, Baron Eduard von der Heydt (1882–1964), banker, collector and connoisseur, sponsored the refurbishing of some rooms adjacent to the existing East Asian Art Collection to house Chinese Buddhist sculptures from his famous collection which he loaned to the museum. He also lectured on his collection at a meeting of the Society (Fig. 15). After World War II (1952) the baron donated his most spectacular collection to the Museum Rietberg in Zurich/Switzerland.

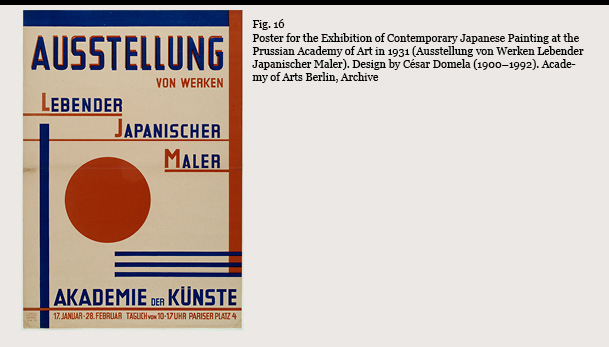

Two years after the Chinese exhibition of 1931, the Academy witnessed another East Asian Art exhibition mounted in collaboration of the Prussian Academy of the Arts and the East Asian Art Society (figs. 16–17). The show which was also presented to the Japanese public in Kyoto and Tokyo for short periods before it travelled to Germany exhibited contemporary Japanese painting.

Two years after the Chinese exhibition of 1931, the Academy witnessed another East Asian Art exhibition mounted in collaboration of the Prussian Academy of the Arts and the East Asian Art Society (figs. 16–17). The show which was also presented to the Japanese public in Kyoto and Tokyo for short periods before it travelled to Germany exhibited contemporary Japanese painting.

More than 22,000 visitors came to see the show which afterwards travelled to Düsseldorf and Budapest/Hungary. 11 works from the exhibition were later donated to the Berlin museum. Among these was the Nihonga-painting by Yuki Somei, “Mountain in clouds”, executed in ink and colours on silk and dating to 1930.

More than 22,000 visitors came to see the show which afterwards travelled to Düsseldorf and Budapest/Hungary. 11 works from the exhibition were later donated to the Berlin museum. Among these was the Nihonga-painting by Yuki Somei, “Mountain in clouds”, executed in ink and colours on silk and dating to 1930.

In 1934 the Prussian Academy of the Arts and the East Asian Art Society mounted yet another exhibition which attracted 13,000 visitors. One of the foremost Chinese painters of this time, Liu Haisu (1896–1994, Fig. 18) came as the Chinese government’s representative to Berlin as the curator of the show. Three years before he had already organised a smaller-scale exhibition of contemporary Chinese painting at the China Institute in Frankfurt am Main. 274 paintings by 163 contemporary Chinese artists were on display in Berlin and subsequently the Chinese government donated 16 of the paintings which represent the work of 14 artists to the museum in 1935.

While almost all of the Japanese paintings donated after the show in 1931 are still extant in the Berlin Asian Art Museum, the donations from the Chinese government are part of those 90 percent of the pre-war collection (more than 5,000 objects) which the so-called trophy commission of the Soviet army took to the Soviet Union at the end of World War II and which is still kept back.

Among the various activities of the Society besides a very ambitious lecture programme was a most successful group excursion with 350 members of the Society to the Great China Exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London from February 8 to February 16, 1936.

A period of decline

The decline of the Society began in 1938, marked most conspicuously by the disgraceful exclusion of many Jewish members who had been among the most active. Jewish members of the board, also enthusiastic collectors of East Asian Art with outstanding merits like the Deputy President Herbert von Klemperer (1878–1951) and the Treasurer Herbert Ginsberg (1881–1962) resigned and soon after left Germany. William Cohn, who had co-edited the Ostasiatische Zeitschrift with Otto Kümmel for 25 years, had to end his career in Germany; he got a monetary compensation and emigrated to England.

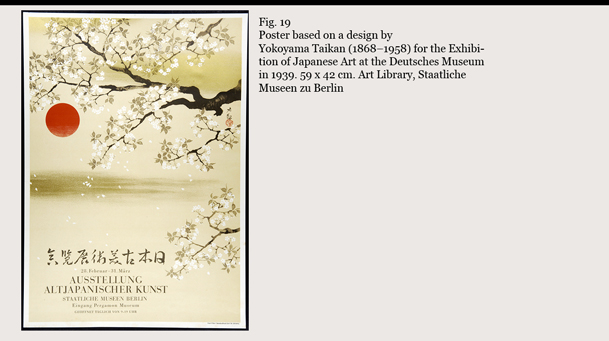

The last major exhibition of the Society and the museum before World War II took place in 1939 and was devoted to ancient Japanese art (Fig. 19), which was a field that Otto Kümmel was particular well acquainted with. Close political ties between Germany and Japan gave impetus to realise an extraordinary, high-ranking art exhibition which included no less than 29 national treasures.

As the exhibition halls on Pariser Platz were by this time already occupied by Hitler’s minister Albert Speer and the Academy dislocated, Kümmel, who was by now General Director of the State Museums in Berlin had to look for another venue. He found it in the so-called “German museum” (today’s Pergamon museum) on Museum Island. With some 70,000 visitors, the exhibition was very successful. Politically, it was used as a platform for propaganda by the Nazi regime, but from an art historical point of view, Kümmel managed to mount an exhibition of Japanese art, which in terms of aesthetics and refinement was never seen before and never again surpassed outside of Japan.

As the exhibition halls on Pariser Platz were by this time already occupied by Hitler’s minister Albert Speer and the Academy dislocated, Kümmel, who was by now General Director of the State Museums in Berlin had to look for another venue. He found it in the so-called “German museum” (today’s Pergamon museum) on Museum Island. With some 70,000 visitors, the exhibition was very successful. Politically, it was used as a platform for propaganda by the Nazi regime, but from an art historical point of view, Kümmel managed to mount an exhibition of Japanese art, which in terms of aesthetics and refinement was never seen before and never again surpassed outside of Japan.

On May 13, 1942 the Society which had at this time had 404 members held its last General Meeting.

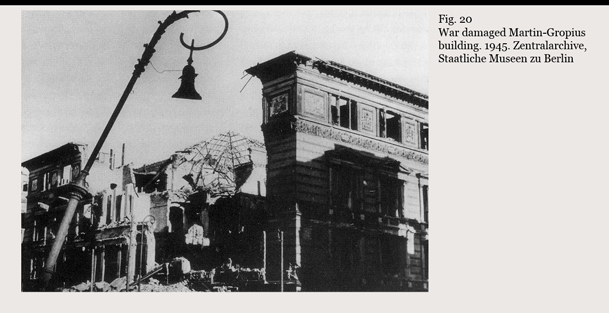

World War II was a catastrophe for the museum and the Society and brought terrible loss and disruption. Ninety percent of the museum collection had been stored in a bunker near Berlin’s zoo during the war and was confiscated and carried away by the trophy commission of the Soviet army as “war booty” at the end of the war. The museum building was destroyed (Fig. 20) and with it about five percent of the collection was lost. The famous library, regarded as the best outside East Asia, burnt down completely. Only some 300 objects predominantly Chinese and Japanese paintings, selected pieces of Chinese applied arts as well as Korean and Japanese tea ceramics had been moved to safety westwards and stored in underground mines where they survived.

New Beginnings in Berlin-Dahlem in Post-war Germany

The Society was dissolved in 1955 and with the remaining financial funds acquisitions were made in an effort to re-establish the collection. The objects that had been moved to safety to the West returned to West-Berlin in 1957 and constituted the core of the collection that was gradually rebuilt in the second half of the 20th century. Leopold Reidemeister, Director General of the State Museums in Berlin-West from 1957 to 1965, who before World War II was working with Otto Kümmel and William Cohn in the East Asian Art Collection, appointed Roger Goepper (1925–2011) as director in 1959 and the museum managed to start a new in Berlin-Dahlem in 1970 (Fig. 21) under Beatrix von Ragué (1920–2006) as director. The photographs show views of the sections for Japanese painting and for Religious Art of East Asia and Chinese applied arts in the new galleries by the architect Fritz Bornemann (1912–2007) which opened on October 21, 1970.

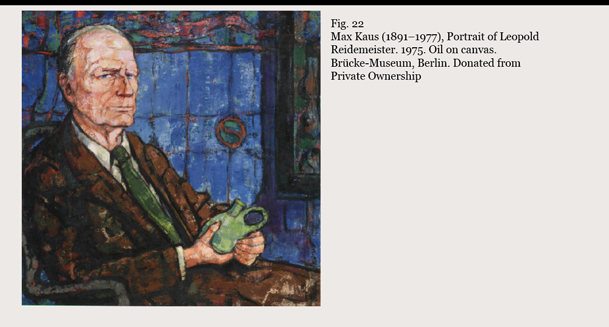

A small circle of collectors and connoisseurs around Leopold Reidemeister met at the museum from time to time and the idea of re-establishing the Society gained momentum. The portrait of Leopold Reidemeister (Fig. 22) painted by Max Kaus in 1975 shows him holding a favourite piece from his small private collection in his hands, a Chinese green-glazed pilgrim bottle which dates to the Liao dynasty (916–1125).

On December 6, 1990 the Society started anew with 17 founding members under the name German East Asian Art Society (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ostasiatische Kunst) and with the author and former diplomat Erwin Wickert (1915–2008) as president. Unlike its predecessor the Society now also started to build up a collection of its own to be on loan to the museum.

After the reunification of Germany the collections of the Berlin state museums which had been divided between East and West Berlin were gradually united. On January 1, 1992, the former West and East Berlin collections of East Asian Art and Culture were brought together in Dahlem. About 75 per cent of the objects of the post-war East Berlin collection which consisted mostly of works of folk art were transferred to the East Asian department of the Museum of Ethnolology also housed in Dahlem. When the Museum of Islamic Art in Dahlem returned to Museum Island to be amalgated with its Eastern counterpart, the Museum of East Asian Art was able to more than double its exhibition space in Dahlem (1800 square meters) and developed a new concept for presenting the collection. After extensive renovations and after being closed for two years the Museum reopened on October 13, 2000.

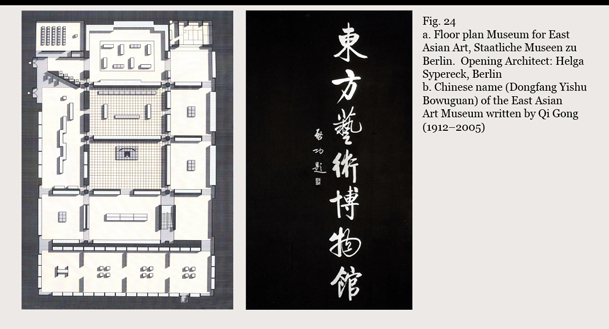

Private patronage again was instrumental in realising this ambitious project. The promise of the connoisseur and art dealer Klaus F. Naumann (born in Berlin 1935, Fig. 23) based in Tokyo and Santa Barbara, California to give his private collection of Japanese painting and East Asian lacquerware as permanent loan facilitated and promoted the grand renovation. In preparation for the project, the Berlin architect Helge Sypereck had inspected art museums in East Asia, the United States and Europe and developed a new concept for the Berlin collection in close cooperation with the Museum of East Asian Art under its director Willibald Veit (b. 1944).

A fundamental issue for the museum was the aesthetic autonomy of a work of art which had to be respected. The focus should be on single objects to be adequately appreciated by the visitors who perceived their aesthetic quality. A special feature of the presentation was the three-monthly change of the objects from the core collection of the museum, calligraphy and painting as well as materials which are light-sensitive like lacquer and textiles, which for conservational reasons were also rotated on a quarterly basis. This continually provided the visitors on repeated visits with new facets of the collection.

Eight square pillars with open corners (Fig. 24) on the floor plan defined the space of the new museum which measured 35 by 52 meters (ca. 1,800 square meters). By applying this scheme, the individual galleries gained a certain amount of transparency and the orientation of the visitors was facilitated. The entrance area, two of the large central galleries and the transition areas between the galleries are laid out in grey slate, all other galleries are laid out in beech which was also used for the panelling of the showcases. The Chinese calligraphy on the right gives the name of the museum (Dongfang Yishu Bowuguan) and was written for the occasion by the renowned calligrapher Qi Gong (1912–2005).

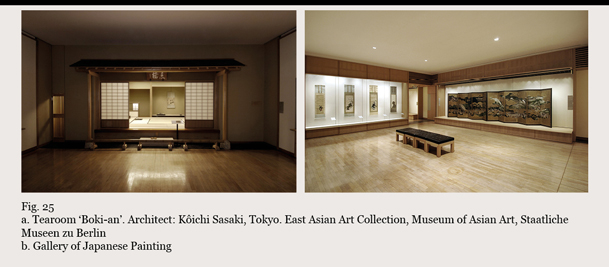

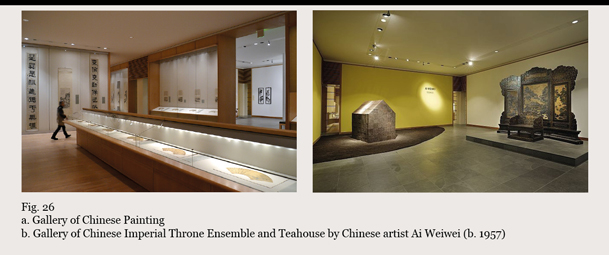

A new feature (Fig. 25) was the installation of a Japanese Tearoom named “Boki-an” designed by the Tokyo Architect Kôichi Sasaki. The photographs (Fig. 25 b) show views of the sections for Japanese Painting and Chinese Painting A more recent view (Fig. 26) shows the Gallery with the Chinese Imperial Throne ensemble from the Kangxi period, 17th c., and juxtaposed the Teahouse, created by the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei (b. 1957), which dates from 2009, on loan to the museum at the time by the Berlin private collectors and members of the Society, Dieter and Si Rosenkranz.

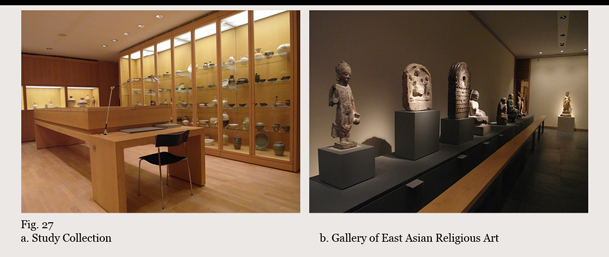

The next picture (Fig. 27) illustrates another new feature integrated into the exhibition space, a study collection on the upper floors.

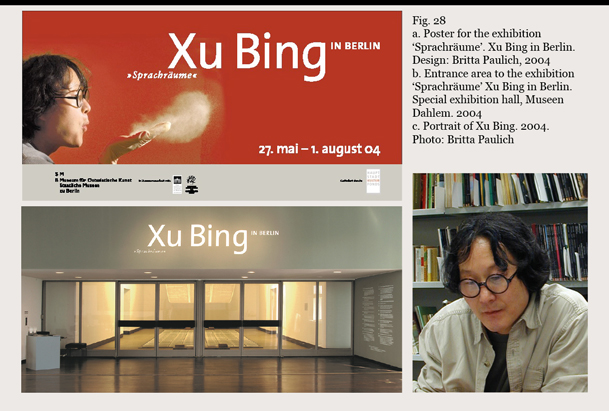

In 2001 the Society also re-launched the East Asian Journal (Ostasiatische Zeitschrift) and resumed exhibitions with the museum and partner institutions. A new focus was contemporary East Asian Art and the first major show took place in 2004, presenting the works of Chinese artist Xu Bing (b. 1955) (Fig. 28).

Xu Bing spent the Spring semester of 2004 as the inaugural Coca-Cola Fellow at the American Academy in Berlin and a special exhibition in the Dahlem museum was his main project. A Berlin collector of contemporary art, Erika Hoffmann, provided the artist with a studio. The Society gave organizational support. Laurin Würdig contributed the exhibition architecture and Britta Paulich the graphic design, both members of the Society which has been headed by Mayen Beckmann (b. 1948) as president since 2006. Uta Rahman-Steinert from the staff of the museum curated the show.

In the work of Xu Bing one of the main focuses is on the issue of Chinese calligraphy which is the earliest form of fine art in China. The potential of this great art form is magnificent and Xu Bing explores it artistically in many – often surprising and innovative ways. His “Book from the Sky” (Fig. 29) was represented as entree to the show. For this installation Xu Bing first gained international recognition and had worked on it more than four years (1987–1991) inventing some 4000 characters that look like Chinese characters but are invented and illegible.

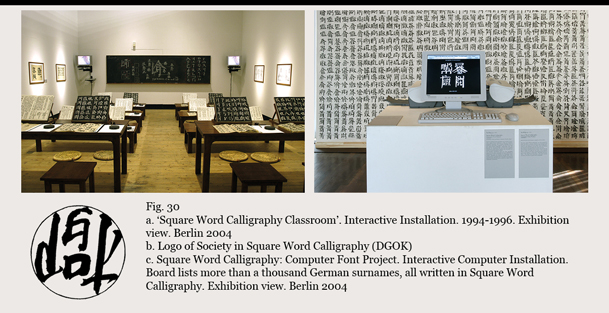

Integrated into the exhibition was also the so-called “Square Word Calligraphy Classroom” (Fig. 30) originally developed from 1994 to 1996. Words with Latin letters written in the Chinese way with brush and ink are fitted into a square resembling Chinese characters. An interactive computer installation was installed outside the exhibition hall called “Square Word Calligraphy: Computer fond project”. On the computer visitors could type their names and have it printed out in their new Square Word Calligraphy form. Also installed was a large board which listed more than a thousand German surnames in Square Word Calligraphy.

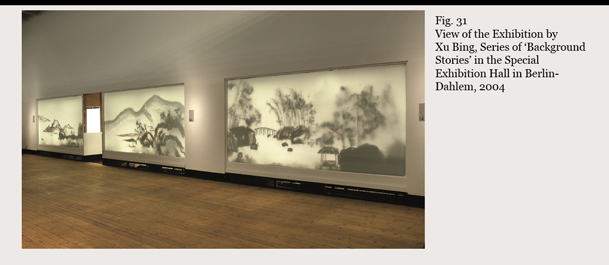

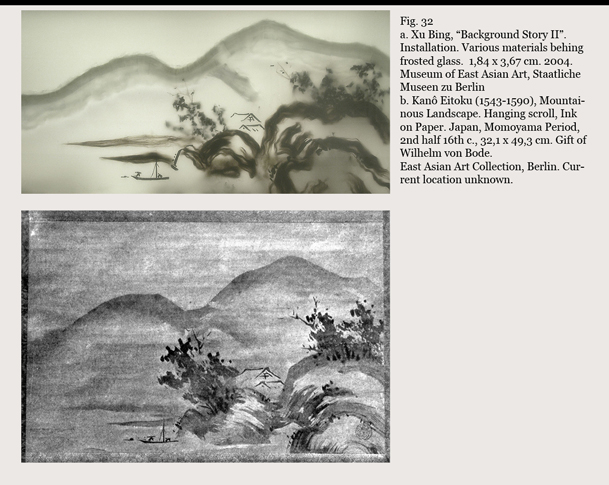

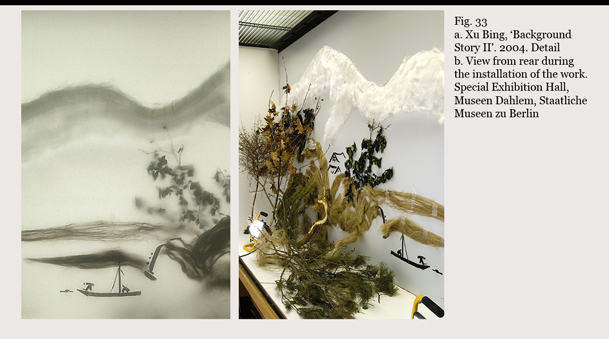

One of the most fascinating works in the exhibition reflected the history of the Museum collection (Fig. 31). In his series of installations called “Background stories” Xu Bing refers to the loss of about 5,400 works of art from the collection, which were – as mentioned already – taken to the Soviet Union by the Red Army in 1945. After studying still existing acquisition file cards and photos of the works lost, Xu Bing chose three paintings from these works and used them as inspiration for his installations in the Dahlem special exhibition hall.

Through frosted glass panels the image of a landscape appears (Fig. 32), based on a lost painting from the collection. The example chosen is a landscape by Kanô Eitoku from the 2nd half of the 16th century executed in ink on paper (32,1 x 49,3 cm).

A passageway between the showcases (Fig. 33) allows the visitors to look behind the scene. Here they realize that the work of art is composed of very simple materials: dry twigs and branches of pine trees, modelling clay and cotton wool – all held together by sticky tape and fishing line. Thus the visitors realize that what they perceived from the front was an illusion.

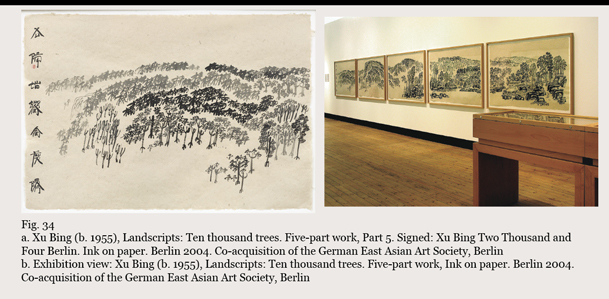

During his time of residence in Berlin Xu Bing also produced a five-part work of art called “Ten thousand trees”, executed in ink on paper (Fig. 34) which was co-acquired by the East Asian Art Society. The slide shows the complete series in the exhibition and part 5 with his signature in Square Word Calligraphy: Xu Bing Two Thousand and Four Berlin. Ideas for his “Landscripts” gained momentum back in 1999 when Xu Bing visited Nepal. In the “Landscripts” Xu Bing unites landscape painting and calligraphy as he uses written characters to “write” landscape elements such as mountains, streams, cliffs and stones and trees.

Acquisitions by the Society which counts 467 members as of April 2018 now amount to 87 that can be viewed online (www.dgok.de/Erwerbungen). Illustrated on figure 35 are three examples. The fine Chinese tapestry (kesi) with lotus and phoenix design from the early Ming period (14th/15th c.) was acquired in 2014. The two paintings illustrated are by women artists. The Chinese bird painting is by Cai Xiaoli (b. 1956), ink and colours on paper, and was donated by a member of the Society in 2016. The Japanese hanging scroll showing maple in autumn by Morimura Ôkei (after 1805–?), ink and colour on silk, was donated by another member of the society last year. A motif from this work of art was used for this year’s membership card of the German East Asian Art Society.

Moving the Dahlem Collections to the Humboldt Forum: Future Perspectives

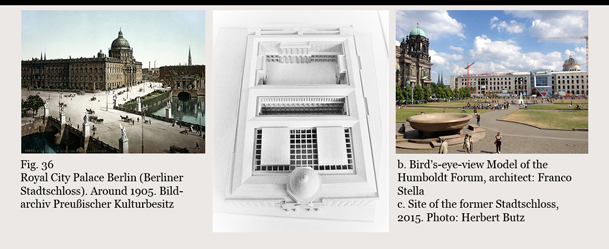

Soon after the successful opening of the two non-European art museums in Dahlem in 2000 – the Museum of Indian Art housed in the same building was also thoroughly redesigned and merged with the Museum of East Asian Art in 2006 under the name Asian Art Museum – a suggestion by the President of the Preußischer Kulturbesitz Foundation, Klaus-Dieter Lehmann, produced further plans for the extension of Dahlem in a new direction. Lehmann brought the Dahlem collections of the Ethnological and the Asian Art Museum into the discussions over the future of the former City Palace (Stadtschloss) site (Fig. 36) at the heart of Berlin, which borders on the Museum Island World Heritage Site.

Under the umbrella of a so-called “Humboldt-Forum” these collections would be installed at the former Stadtschloss site as a non-European counterpart of the European collections just across. The image shows on the upper right a bird’s-eye-view of the model by the Humboldt-Forum Architect Franco Stella. Since January 9, 2017, the Asian Art Museum and the Ethnological Museum in Dahlem are closed and preparing the move into the Humboldt-Forum. Opening is scheduled for late 2019. Hopefully, a great legacy as far the East Asian Art Collection is concerned will not be risked. In a transformational period such as this, a Friends’ Society such as the East Asian Art Society in Berlin is all the more important as an instrument to counterbalance and raise its voice for art’s sake.

Herbert Butz

Member of the Board

*Herbert Butz (b. 1949) studied Sinology and East Asian art history at the Universities of Heidelberg and Zurich/Switzerland. After graduating from Heidelberg University he worked as curator at the East Asian Department of the Museum for Applied Arts in Frankfurt and lectured at Heidelberg University. In 1988 he joined the Museum of East Asian Art, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, and served as head of the East Asian Art Collection and Deputy Director of the Asian Art Museum retiring in 2014. He is a founding member of the East Asian Art Society in Berlin (re-established in 1990) and member of the board.

Selected bibliography (in alphabetical order)

• Ausstellung Chinesischer Kunst veranstaltet von der Gesellschaft für Ostasiatische Kunst und der Preußischen Akademie der Künste Berlin. 12. Januar bis 2. April 1929. Berlin 1929.

• Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin und Landesbildstelle Berlin (Hrsg.), Berliner Lebenswelten der zwanziger Jahre. Bilder einer untergegangenen Kultur photographiert von Marta Huth, Frankfurt/Main: Eichborn 1996.

• Mayen Beckmann und Herbert Butz, „25 Jahre Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ostasiatische Kunst,“ in:Ostasiatische Zeitschrift, Neue Serie,Nr. 30 (Herbst 2015) pp. 16–25.

• Herbert Butz, „In den Fernen Osten emigriert“. Leopold Reidemeister und die Ostasiatische Kunstsammlung’, in: Leopold Reidemeister. Ein deutscher Museumsmann, 1900-1987. Hrsg. von Magdalena Moeller. Beiträge von H. Butz, H.G. Hiller von Gaertringen, K. Hiller von Gaertringen, D. Schöne, I. L. Severin. Hirmer 2017, pp. 72-112.

• Herbert Butz, Wege und Wandel. 100 Jahre Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst. Mit Beiträgen von Wolfgang Klose und Hartmut Walravens. Berlin: Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst 2006.

• Herbert Butz, „Awakening Interest: Pioneering Exhibitions of East Asian Art in Berlin in the Early 20th Century“, in: Orientations Bd. 37, Nr. 7 (Oktober 2006), pp. 40–43.

• Herbert Butz, „The Aesthetics of Collecting and Presenting East Asian Art in Berlin. Some Historical Perspectives“, in: The 3rd Symposium on Oriental Aesthetics and Arts, November 8, 2001. Taipei: National Museum of History 2002, pp. 49–82.

• Herbert Butz, „Die Ausstellung wird gemacht“. Die große chinesische Kunstausstellung in der Akademie der Künste im Jahre 1929“, in: Museums-Journal 4, 14. Jg. (Oktober 2000), pp. 20–23.

• Patrizia Jirka-Schmitz, „Das Land selbst ist himmlisch.“ Wilhelm Solf und seine Sammlung japanischer Kunst’, in: Ostasiatische Zeitschrift, Neue Serie, Nr. 30 (Herbst 2015) pp. 41–53.

• Patrizia Jirka-Schmitz, „Der Sammler Herbert M. Gutmann und der Herbertshof“, in: Mitteilungen der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Ostasiatische Kunst, Nr. 30 (Oktober 2000), pp. 9–23.

• Patrizia Jirka-Schmitz, „Die Gesellschaft für Ostasiatische Kunst (1926–1955)“, in: Mitteilungen der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Ostasiatische Kunst, Nr. 2 (Oktober 1992), pp. 1–11.

• Frauke Kempka, „Kunstgenuss im Dienste der Propaganda. Die Ausstellung Altjapanischer Kunst in Berlin 1939“, in: Ostasiatische Zeitschrift, N.S. Nr. 8 (Herbst 2004), pp. 22–32.

• Wolfgang Klose, „Dr. William Cohn. Gelehrter Publizist und Advokat Asiatischer Kunst“, in: Ostasiatische Zeitschrift, N.S. 12 (Herbst 2006), pp. 31–40.

• Wolfgang Klose, „Otto Kümmel and the Development of East Asian Art Scholarship in Europe“, in: Orientations, Volume 31, Number 8 (October 2000), pp. 113–117.

• Kuwabara Setsuko, „Zwei bedeutende Ausstellungen japanischer Kunst in den 30er Jahren dieses Jahrhunderts“, in: Wolfgang Brenner u.a. (Hrsg.), Berlin-Tokyo im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, Berlin 1997, pp. 283–292.

• Leopold Reidemeister, „Erinnerungen an das Berlin der zwanziger Jahre“, in: Wissenschaften in Berlin. Gedanken, Berlin 1987, pp. 187-194.

• Vivian J. Rheinheimer (Hrsg.), Herbert M. Gutmann 1879–1942. Bankier in Berlin. Bauherr in Potsdam. Kunstsammler. Leipzig: Koehler & Amelang 2007.

• Willibald Veit, „Die neue Ostasiatische Zeitschrift“, in: Ostasiatische Zeitschrift, N.S. Nr. 1 (Frühjahr 2001), pp. 5-7.

• Hartmut Walravens, „Ostasiatische Zeitschrift“ (1912–1943), „Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Ostasiatische Kunst“. Bibliographie und Register, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag 2000 (Orientalistik Bibliographien und Dokumentationen, Band 10).